You’ve heard the buzz: A Wrinkle in Time, based on the classic children’s book by Madeleine L’Engle (1918–2007), hits theaters this week as a $100 million Disney movie.

A lot more than money is riding on the film’s success. Not only is the sci-fi novel beloved by millions of readers—since winning the 1963 Newbery Medal, it has sold upwards of 16 million copies—but its author was one of the most adored writers of Christian faith in recent history.

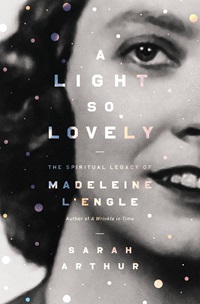

As I’ve learned while writing her spiritual biography (A Light So Lovely: The Spiritual Legacy of Madeleine L’Engle, which releases in August), her fans among millennials and my own Generation X, in particular, are as vast as the cosmos she so loved. For many who struggle with faith and doubt, L’Engle has become a kind of patron saint for the wavering, the wondering, and the wounded.

No pressure, Hollywood.

This new adaptation of Wrinkle, directed by the irrepressible Ava DuVernay (Selma, 13th, Queen Sugar), stars no less than Oprah Winfrey, Reese Witherspoon, Mindy Kaling, and Chris Pine. Frozen’s Jennifer Lee adapted the storyline for the screen, and along the way the main characters have been creatively recast as a multiracial family. DuVernay herself is the first female director of color to oversee a budget this size.

Newcomer Storm Reid plays Meg Murry, the story’s teen protagonist, who is sent by a triad of angelic beings (Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which) on a quest to find her missing scientist-father trapped behind a dark force in the universe. The “Mrs” trio teaches Meg and her companions how to fold, or wrinkle, the space-time continuum so they can skip from galaxy to galaxy, planet to planet—a concept called tessering.

“I think you have to prepare yourself that the movie will look different than the book,” producer Catherine Hand told me. “I hope people who love the book don’t just focus on the trees and not see the forest.” Hand first sat down with L’Engle in 1979 to discuss bringing the story to the big screen and now, nearly 40 years later, is seeing her dream become reality. “The movie is going to look different because it had to look different,” Hand explained. “Too many filmmakers, writers, directors, all sorts of creative talent have been influenced by Wrinkle for 50 years. Some of the visuals that we hold dear in Wrinkle we’ve already seen on film. We had to take the essence of the emotional story—e.g., why did this happen in the book?—and explore how to give it a new look but with the same meaning.”

The question many are wondering is whether the “essence” and “meaning” will include the spiritual themes that were vital to L’Engle’s Christian faith.

Asking ‘Cosmic Questions’

During the 1950s, as a 30-something transplant from New York City to rural Connecticut, L’Engle struggled to balance writing, child-rearing, and small-town life. She also wrestled with what she called “cosmic questions”: Does God exist? Why are we here? Do we exist after death? Well-meaning pastors encouraged her to read German theologians (she rarely ever named which ones, exactly, although philosopher Immanuel Kant is a strong contender). But she found no solace there. Such theology, for L’Engle, emphasized a limited God definable by human categories, a concept wholly at odds with the awe-inspiring, star-strewn universe she saw at night while walking her dogs.

By contrast, it was the wonder and humility of scientists, especially theoretical physicists like Max Planck and Albert Einstein, who eventually convinced her to become a Christian. If the Creator of a vast and surprising cosmos could love this small planet enough to become one of us, then—despite her ongoing questions—that was a faith worth clinging to. As L’Engle said in a 1979 interview with Christianity Today, “I believe that we can understand cosmic questions only through particulars. I can understand God only through one specific particular, the incarnation of Jesus of Nazareth.”

Thus, “A Wrinkle in Time was my rebuttal to the German theologians,” L’Engle wrote in Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art (1980). Her protagonist—angry, nerdy Meg Murry, in many ways a portrait of L’Engle herself as a girl—is unwilling and unable to conform to cultural expectations, to the usual categories by which we define human worth. By the end of her story, Meg must confront the source of the darkness that’s at war with the light: a pulsing, disembodied brain that threatens to absorb everything into the pattern of itself. Its goal is to annihilate the created particularity of each unique thing, down to the smallest particle.

For anyone who’s ever fallen asleep reading German theology (raises hand), this is a stirring concept. If faith can be reduced to an intellectual exercise, to mere agreement with certain principles and precepts, then all you have left is knowledge without agency, without mercy or compassion. All you have is a disembodied mind, out there in the universe, coldly detached from human suffering. And a thing without a body could never, ever love you the way God in Christ does.

Click here to read more.

Source: Christianity Today

Comments